2021.08.06

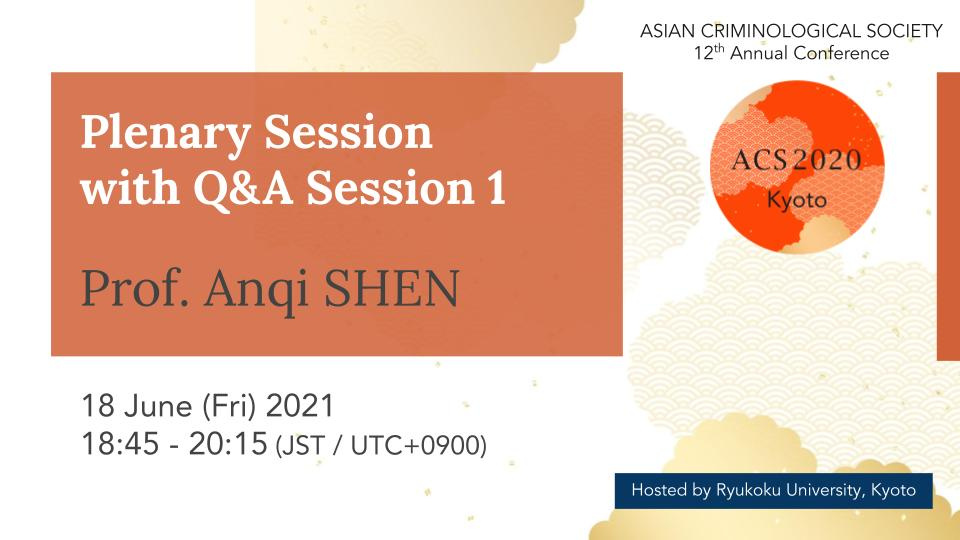

[Report of the ACS2020] Plenary Session with Q&A Session_Prof. Anqi Shen

Internal Migration, Crime, and Punishment in Contemporary China: Migrant women and their involvement in criminalty

The Asian Criminological Society 12th Annual Conference (ACS2020), hosted by Ryukoku University, was held online for four days from June 18 to 21, 2021. The purpose of the conference, the second of its kind to be held in Japan after the 2014 Osaka conference, was to promote the growth of criminology in Asia and Oceania, and to promote academic exchange with advanced regions of criminology such as the United States and Europe.

>> ACS2020 Program https://acs2020.org/program.html

The overall theme of the conference is "Crime and Punishment under Asian Cultures: Tradition and Innovation in Criminology". The aim was to promote understanding of the social systems and culture and measures against crime and delinquency in Japan, which is said to be "the country with the least crime in the world".

The following is a summary of the Plenary Session with Q&A Session, which was held live streaming at the conference.

- Plenary Speaker: Anqi Shen (Professor of Northumbria Law School, Northumbria University, United Kingdom)

- Chair: Setsuo Miyazawa (Professor Emeritus, Kobe University, Japan; ACS President)

- Date: 18:45-20:15, 18 June, 2021

- Keywords: Chinese domestic migrants, female migrant workers, pyramid scheme crime, neoliberalism, household registration system, tension theory, feminist theory

Anqi Shen (Professor of Northumbria Law School, Northumbria University, United Kingdom)

China’s economic reforms – or its ‘turn towards neoliberalism’ – began in the late 1970s, fuelled a trend of urbanization and mass migration within the country, largely from rural regions to more economically developed urban areas. Women are part of the internal migration process among thousands of migrant labourers. With this exodus of ‘peasant workers’ from villages to towns and cities, came new challenges in a rapidly changing society. In metropolises and wider urban settings, rural migrants – men and women – are marginalised, and marginalisation makes individuals vulnerable and prone to lawbreaking. Female migrant workers, in particular, are under enormous pressure in the polarised and gendered social conditions. In migration studies in relation to China, much has been done to explore women’s experiences in the rural-to-urban migration: their opportunities, struggles and hopes in cities where they live as outsiders. In socio-legal and criminological research, past studies focusing on China have looked at the overall causes of migrant criminality, drug problems among migrant youths, victimisation of ‘peasant labourers’, and inadequacy in public policy in response to the criminogenic, structural factors in migrant offending. Nonetheless, little attention has been paid to the subjective experience of migrant offenders, and women’s involvement in lawbreaking is largely neglected. In this mini lecture, I will examine criminality involving female migrants in the context of a neoliberal society. I will use a case study to explore, from a feminist perspective, internal migrant women’s engagement in illegal pyramid selling, which is increasingly prevalent among female lawbreakers in China today. I will briefly introduce the pertinent local socioeconomic setting before detailing the case study to discuss women’s entry into illegal pyramid selling, their motivations, the roles they play in the criminal operation and, of course, their gains and losses as a result of participation in crime. This is hoped to help reveal links between female criminality, neoliberal subjectivities, self-enhancement, greed – neoliberalism’s maladies – social exclusion and gender biases that female rural migrants experience in the new, urban milieus to which they do not belong and have no formal and real membership.

Summary of the Q&A Session

Question 1: The fact that you have interviewed prisoners in China is surprising in itself. Interviewing prisoners is not an easy task even in a country with a low authoritarian character. I would like you to explain how you gained access.

Answer 1: It was indeed a difficult survey and required a great deal of commitment, determination, hard work, and luck. I was a member of the Center for the Rule of Law organized by the local government in the study area, and this study was part of a larger one on the situation of migrant workers, which was funded by the local government. In addition, I had been involved in criminal justice for more than ten years before coming to the UK, and I was also a lawyer, so I had contacts and was trusted. Also, the prison had a women's facility, which was ideal for the research. However, the sample size had to be reduced, and the interviews were always tense because of the possibility that they might be stopped at any moment. Moreover, the prison was located in a remote mountainous area, and it was difficult to drive there at night when there was no lighting.

Question 2: You state that the pyramid scheme crimes of the two female inmates you interviewed were "investment activities". What were they investing in? Who created the organization? Were they punished?

Answer 2: The investment targets could be as diverse as health-related products, real estate, or even an island somewhere, but in reality, there was no investment activity going on, and the only purpose was to collect funds from new members. However, it was a normal company in appearance and internal organization, with a receptionist, marketing department, legal department, etc., and the female inmates were not aware that they were operating in an illegal organization at all. There is no established legal interpretation as to what kind of behavior is punishable, and if they engaged in any kind of managerial activity, they could be punished as organizers. Those at the top of the organization have been punished for fraud as well.

Question 3: The female inmates were not aware that their pyramid scheme activity was a crime, but is it possible that they chose this crime over other criminal activities?

Answer 3: The female inmates are first-time offenders, and their participation in the pyramid scheme was not a choice they made in comparison to other crimes, since they believed they had joined a normal company. They may have been aware that they had crossed some boundaries, but they were not aware that they had chosen to commit criminal acts.

Question 4: The two women have been convicted of recruiting new members into the organization, but how long is the sentence? In Japan, the penalty is imprisonment for not more than 3 years or a fine of not more than 3 million yen, or both, for those who established and operated the organization; imprisonment for not more than 1 year or a fine of not more than 300,000 yen for those who recruited as a business; and a fine of not more than 200,000 yen for those who simply recruited. Have they already been released? If they have been released, have they returned to their hometowns?

Answer 4: Under Chinese law, a person who organizes a pyramid scheme organization that results in serious circumstances, such as confinement or suicide, can be sentenced to a fixed term of five years or more and fined, while a person who merely solicited without such serious results can be sentenced to a fixed term of five years or less and fined. One of the women I interviewed was sentenced to six months, and the other to one year. I believe they have already been released, but I cannot get any information about them after their release. However, according to the interviews, they were very confident in their abilities and wanted to take a chance in the city instead of going back home. One in particular had even become a certified public accountant while working for her organization. The idea that one must succeed on one's own is truly neoliberal.

Question 5: It seems clear that the root of the problem lies in the family registration system. Japan also has a family registration system, but it is not a system that restricts social welfare or economic and social opportunities as in China. Has the Chinese government taken any measures to address this situation?

Answer 5: The Chinese government is aware of the problem, but since it does not have the power to help all migrant workers from rural areas, it only takes measures for those with a certain level of education and economic power. It does not cover the less-educated like these women or those from lower-ranked universities.

Question 6: Their behavior could be explained by strain theory, but if they learned the modus operandi, etc., after joining the organization, then differential association theory could also apply.

Answer 6: I think strain theory is more appropriate because these women were not aware that they were doing anything illegal at all. They thought that they were conducting the business of a legitimate company and had no knowledge of the criminal behavior.

Question 7: The reason for their actions might not be neoliberalism, but rather traditional Chinese culture.

Answer 7: The idea that economic success takes precedence over everything else is a product of post-1970’s reforms, and is not at all based on traditional culture. Today, neoliberal ideas are widely shared by the socially disadvantaged, who generally believe that it is their responsibility to improve their own situation and that they should not burden the government, and that they should accept their own unfavorable situation. It is highly unlikely that such a social structure will change in the near future.