2023.06.02

米・ミシガン州立グランドバレー大学の学生と龍大生が合同ゼミを開催【犯罪学研究センター協力/法学部】

「日本の犯罪率の低さ」はどこにあるのか?日米の学生らが文化的、社会的側面から考察

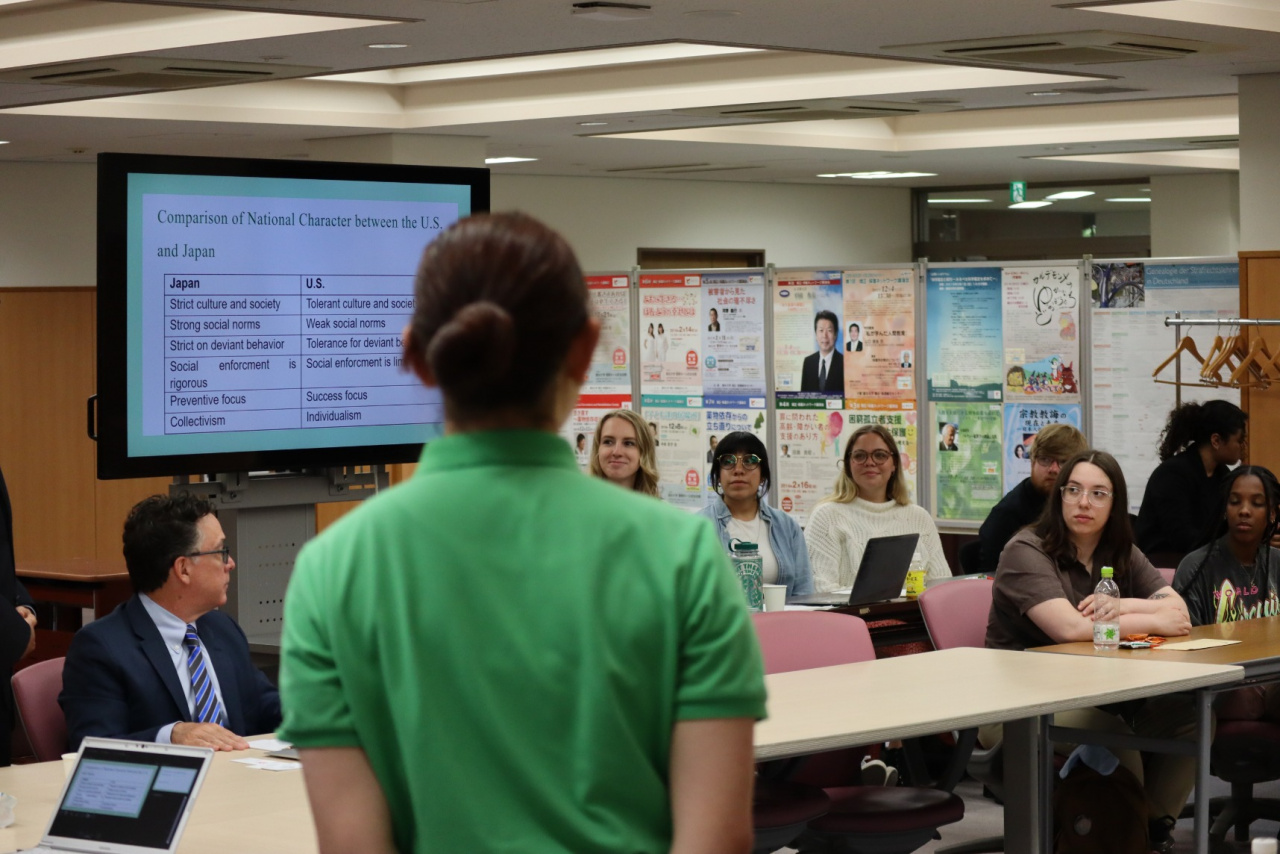

2023年5月24日(水)、龍谷大学深草キャンパス至心館1階で、龍谷大学と米・ミシガン州立グランドバレー大学(以下、グランドバレー州立大学)の学生が、「日本の治安」をテーマに合同ゼミを開催しました(犯罪学研究センター協力)。*1

龍谷大学からは、浜井浩一教授(本学法学部、犯罪学研究センター「政策評価」ユニット長、矯正・保護総合センター長)と、法学部・浜井ゼミ生を中心とした学生5名が参加しました。グランドバレー州立大学からは、15名の学生とJohn Walsh教授、Naoki Kanaboshi(金星直規)准教授が参加しました。両校の学生の理解を補助するために金星准教授には通訳を担当していただきました。そして、特別ゲストとして当センターの嘱託研究員であるASIF Hadas氏(イスラエル/テレアビブ治安判事裁判所・主席判事)が参加しました。

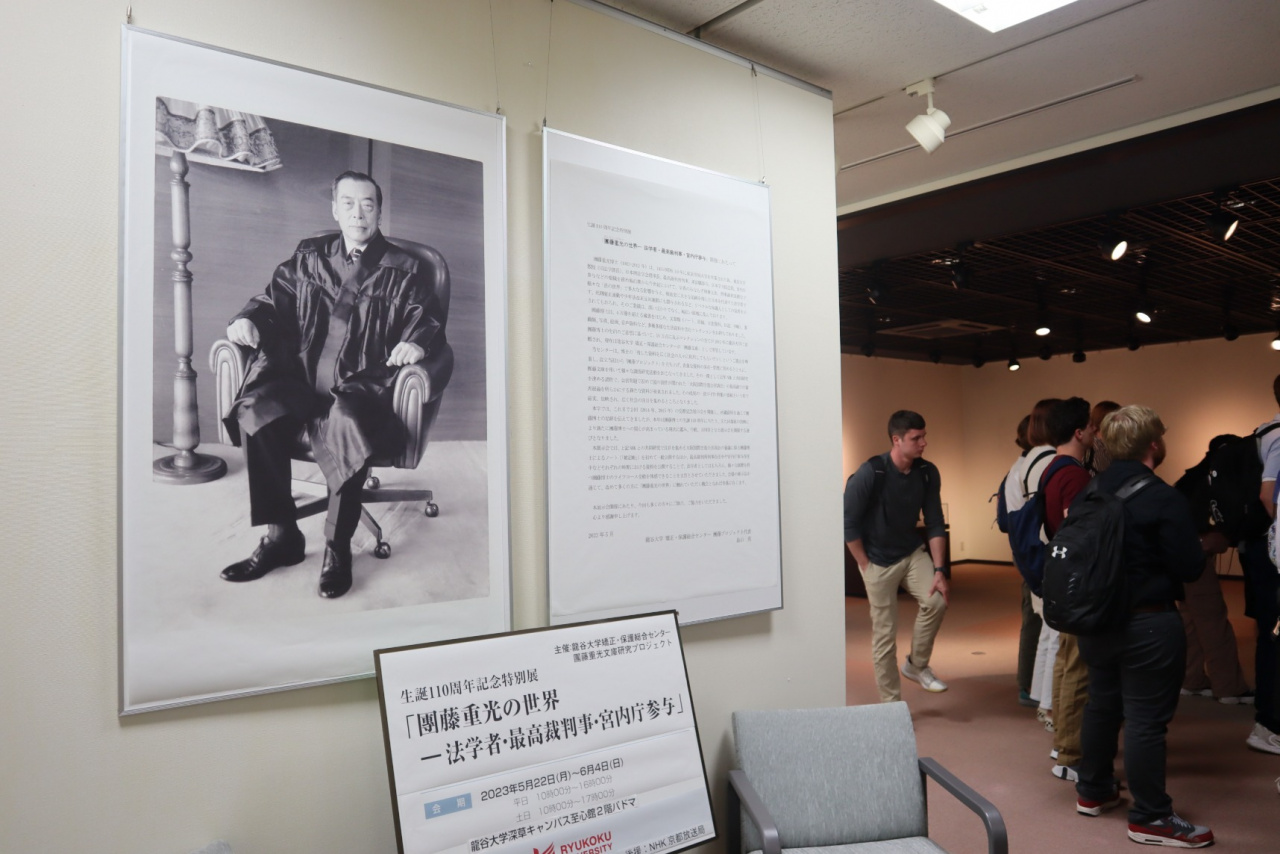

日米学生合同ゼミでの学生報告のあとには、浜井教授が「日本の文化と犯罪状況」について解説する小講義が行われました。最後に両校の学生は、本学で開催中の展示会『團藤重光の世界‐法学者・最高裁判事・宮内庁参与』を鑑賞し交流会を終えました。

今回のイベントでは、HUNT Adam James氏(英国 シェフィールド大学大学院法学研究科・博士課程、犯罪学研究センター嘱託研究員)*2が、龍谷大学の学生らの英語発表に際して、準備の段階からサポートしました。以下では、ハント氏によるイベント参観レポートを紹介します。

[参観レポート(抄訳)]

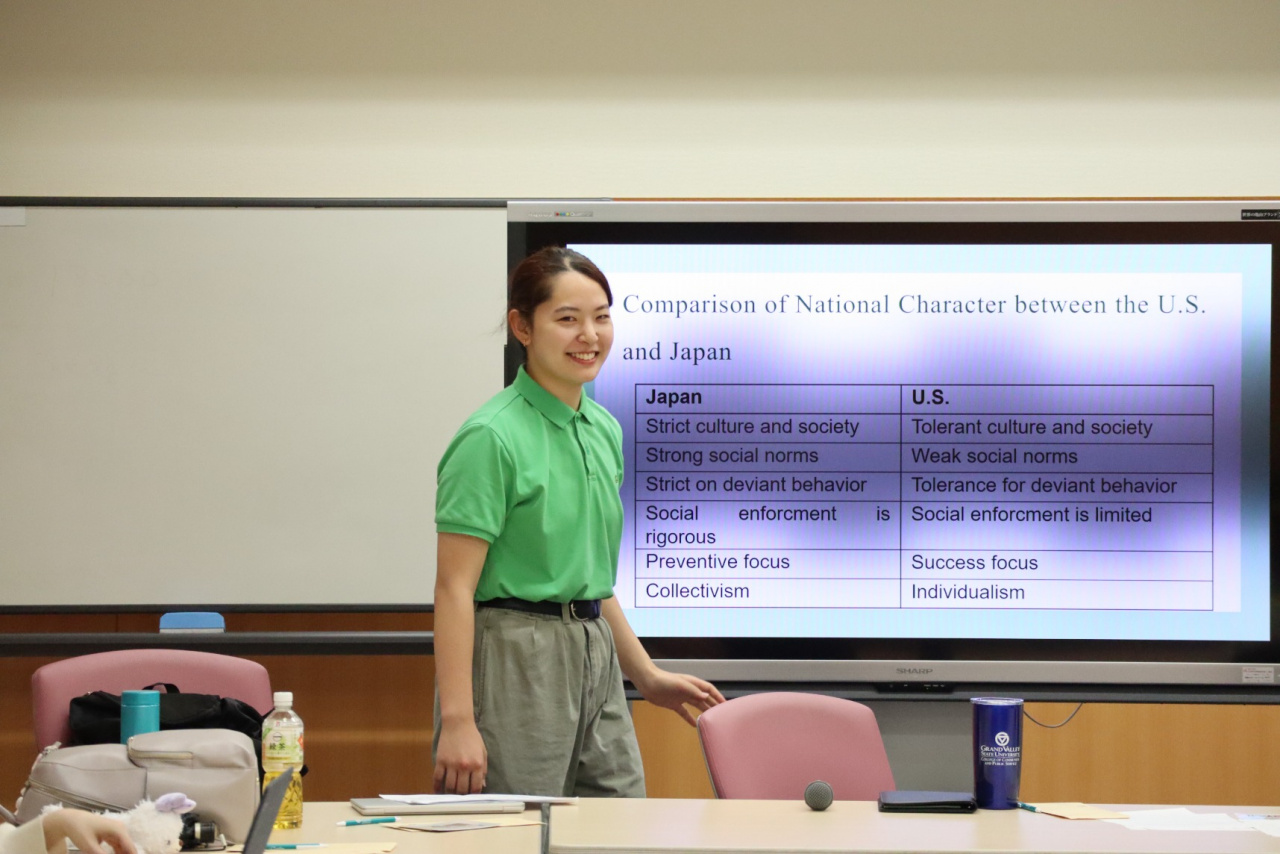

このイベントでは、日米の学生に「日本の犯罪率の低さ」をとりあげ、重要だと思われる要素について発表してもらいました。龍谷大学の学生は、まず日本の銃規制をとりあげました。日本は、アメリカに比べて銃の管理レベルが厳しく、手続きも繁雑なため、銃を持つ人が少ない環境です。そのため、日本は銃に関連する犯罪が少なく、アメリカでは銃が使用されるようなケース(集団暴力行為)も日本では別の手段で行われるようになったと学生たちは主張します。また狩猟用具として銃が使われるケースは限られており、それ以外にも必要な手続き(キャビネットの施錠)があるため、日本人はほとんど銃を目にすることがありません。そのため銃をめぐって政治的な議論がされることもありません。

つづけて学生たちは日本社会の現実の構造について言及しました。自然災害(地震や津波)の多さ、そして文化的に根付いている協力の精神や、日常生活の厳しさがとりあげられました。学生たちは日本の社会空間(職場、公共の場、家庭など)では、評価文化が維持されていると主張します。例えば、お辞儀やビジネスマナー、目上の人への敬意など、社会人に対して非常に特殊な行動を要求します。人々はそのような環境下で失敗や「間違った」行為による結果を避けるために行動します。失敗する行動から遠ざかるように条件付けることによって、個人に影響を与えていることを理論づけます。個人的にも、実際に明らかになっている事実から文化的イデオロギーの再強化の影響を考察することは面白いと思います。日本の文化は、学校教育の中で再生産され、洗練されていく。このような、社会が見落としている重大で単純な点を、学生たちは指摘したのです。非常に興味深いことに、学生たちはこれらの条件がもたらす効果について指摘しました。予防と成功の重視は、失敗や逸脱した行動に対する文化的な嫌悪感や、個人や集団の成功を優先させるために失敗を無視する(成功を推し進める)という形で現れます。最後に、学生たちは集団主義について興味深い指摘をしました。日本の文化は、自分の属するグループの他のメンバーに対するイデオロギー的な優先順位や、協力することを目標とする日本の現実的な条件によって、協力を促進することに注力しています。

報告のあとに質疑応答の時間が設けられました。龍谷大学の学生らは、「もし日本が銃社会になった場合、犯罪率が上がると思うか」という質問に対して、過去の事例を引き合いに出しながら、「日本では犯罪率よりも自殺率があがるのではないか」と答えました。銃が増えたからといって、すぐに犯罪が増えるわけではないという推論は、会場にいる参加者全員の一致した意見でした。私はこの議論で、銃規制の改正がもたらす長期的な影響について考えさせられました。

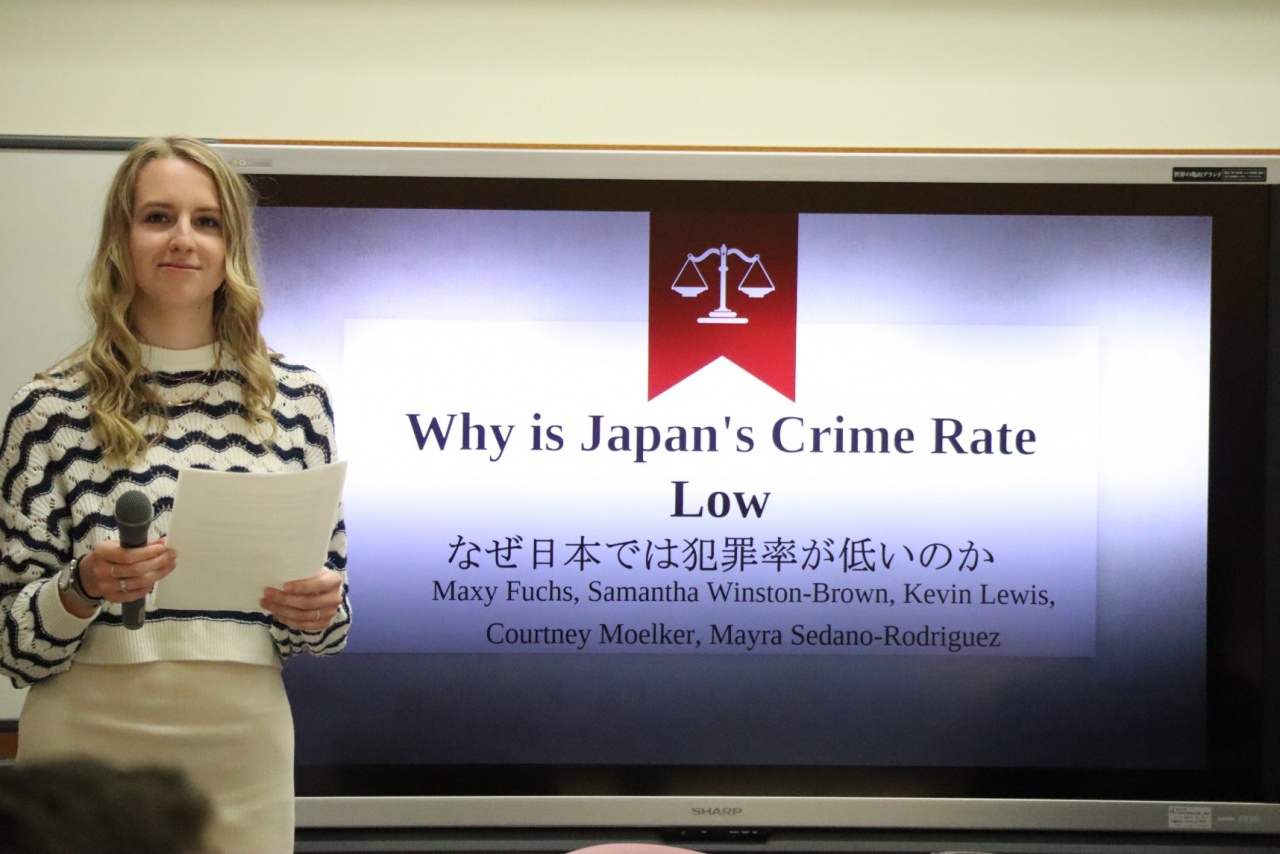

グランドバレー州立大学の学生たちは、日本の文化的特徴について考え、否定的な状況を回避する「Kimochi Shugi:気持ち主義」を提起しました。失敗を回避する社会がもたらす影響について、学生たちは日本側の学生と同じような議論を展開しました。そして、日本における権威の尊重が提起されました。日本社会がどのように責任を共有する環境を維持しているかを説明するために、「名誉」と「家族」というキーワードが使われました。

そして日本の刑事裁判のあり方について話が進みました。日本では、警察が「交番」を通じて地域社会に溶け込み、環境と調和するように設計されている。そして、このようなコミュニティ・ポリスが、人々の法律を守ろうとする気持ちにどのような影響を与えたかについて説明しました。さらに、日本の刑事裁判の有罪率について説明し、起訴の制限から生じる潜在的な影響を明らかにしました。一般的に日本の刑事司法のネガティブな側面と考えられているものについて、日本の刑事司法手続きに乗せないこと(起訴猶予等のダイバージョン)へのポジティブな効果を挙げている点が興味深く感じました。

報告後、ゲストから「警察官のイメージ」について質問が出されました。日米で警察官のイメージに大きな違いがあることが興味深く、両校の警察官志望の学生による回答は素晴らしいものでした。今回の報告を通して「日米の共通点が見つかったのか」を質問したところ、グランドバレー州立大学の学生らは、「まだ研究の過程で、直接の比較は避けたかった」と述べました。文化に目を向けると、常に誘惑に駆られるものです。比較研究というのは、常にデリケートな試みです。その代わり、彼らは日本の状況を理解することに集中し、自分たちの状況をあまり考慮しませんでした。

両講演終了後、Walsh教授からコメントがありました。Walsh教授は、元警察官としての経験と信念から、低い犯罪率は、健康なコミュニティにもたらされ、質の高い医療、刑務所、警察活動、それらが協力的な精神としてコミュニティに影響を与えることが重要であると述べました。

最後に、浜井教授が、日本の犯罪率の低さについて独自の見解を述べました。

浜井教授は、日本の状況(犯罪率の低さ)を、統計データを用いてさまざまな角度から検証し、このテーマがいかに複雑であるかを明らかにしました。説得力のある要因として、若者の人口減少が挙げられました。青少年が減れば、犯罪の中で最も大きな割合を占めることで知られる少年犯罪も減ります*3。人口減少が犯罪率にどのように影響するか、少年犯罪との直接的な関係だけでなく、より多くの段階で考えることができることは注目に値すると思いました。若者の競争をめぐる社会的影響や、少子化対策への重点的な支援など、もっとお話を聞きたかったです。

全体として、このイベントは、2つの学校の垣根を越えた議論のための興味深いプラットフォームを提供しました。この若い研究者たちが、今後も魅力的な批判的議論を展開することを期待しています。

[参観レポート(原文)]

The event featured presentations on the low crime rate in Japan, inviting both parties to present what they feel are important factors related to this topic.

Ryukoku’s students began with an interesting note on the gun control laws in Japan. They explained that the strict level of control over guns and high volume of procedures in comparison to America provided an environment in which guns are not common in the population.

They theorised that this low level of gun use generated less gun related crimes, and situations that normally involved guns in America (acts of mass violence), had different means. In addition, the limited use case of guns as hunting tools and the required procedure outside of that use case (locking cabinets) further reduce the visibility of guns. To the point that political discussion of guns is limited.

As part of this discussion the students brought up painful recent events for both countries, thus showing a commitment to keeping the conversation honest, frank and true to the academic spirt.

The second part of the presentation involved a model of factors that contribute to harmony in Japan.

They began with an interesting note about the practical structure of society in Japan, the frequency of natural disasters (earthquakes and tsunami’s) generating an ingrained cultural spirit of co-operation.

It is interesting to think about how the recent and aggressive expansion of America has shaped its value system in contrast to Japan’s long, isolated and refined cultural practice.

The students then went on to discuss the level of strictness inside Japanese life. Arguing that social spaces (such as the work place, in public or at home) maintained an evaluation culture. For example, companies in Japan demand very specific behaviours of their staff, bowing, formality, respect of higher ups. As such, people operate in such an environment to avoid failure and the consequences of doing something “wrong.”

This was theorised to affect the individual by conditioning them away from failure actions.

Unfortunately, the students were unable to mention the conditions of Japanese schooling given the time constraints. Which I know they wanted to include from my conversations with the students prior to the event. Interestingly, however, this was brought up as a point by the Grand Valley students.

Personally, I find it interesting to consider the re-enforcing effect of cultural ideology when it manifests into practical reality. Japanese culture is re-produced and refined in its schooling. A critical and simple point of society often overlooked noted by these students.

Following this, very interestingly, the students noted the effect of these conditions. ‘Prevention focus’ which is the culturally fostered aversion to failure and deviance in behaviour. And ‘Success Focus’ an ignorance (and arguable fostering) of failure as a way to priorities individual and group successes.

Finally, the students made some interesting points about collectivism. Noting that Japanese culture facilitates cooperation in ideological preference for other members of their group, and by the practical conditions of Japan that make co-operation the goal.

The grand valley students then gave their own presentation.

The students first considered the cultural character of Japan, raising the consideration of kimochi shugi, the avoidance of negative situations. Mirroring the previous presentation, the students made similar arguments as to the effect of a society with failure avoidance built into its structure and ideologies.

The respect for authority in Japan was then raised. Honor and the family were used to explain the how Japanese society maintains an environment in which there is a level of shared responsibility.

The students then moved on to talk about Japanese criminal justice practice.

They discussed the way police in Japan have been integrated into communities via Kohban, buildings designed to match their environment. And the consequence this community policing has had on people’s desire to adherence to the law.

They then moved on to explain the conviction rate of the Japanese courts, identifying the potential effect stemming from limited prosecution. An interesting take on what is commonly considered a negative aspect of Japanese criminal justice, to cite the positive effect on those people that are not provided entrance into the criminal justice system in Japan.

Prof Walsh provided his comments after both presentations.

He talked about his experience as an ex-police officer, and his belief that a low crime rate was routed in healthy communities, with high quality healthcare, prisons and policing being critical when they effect their communities with a co-operative spirit.

Finally, Prof Hamai gave his own presentation on the low crime rate.

This presentation made heavy use of statistical data to examine the question of low crime from many different perspectives. Identifying just how complicated this topic is. A fascinating explanatory factor provided was the declining youth population. With less youth, there is less youth crime which is well known to account for the largest proportion of crime.

I found it remarkable to consider how a declining population state interacts with the crime rate, on more levels than just the direct connection to youth crime. The social effect on competition for young people, and the more focused support to lower volumes of children are factors that I would happily like to hear more on.

Overall, this event provided an interesting platform for discussion across the two schools. I’m looking forward to more engaging critical discussions from these young scholars in the future.

[Note]

Q and A followed the presentation, I’ll note some of the interesting questions.

Grand Valley students: what do you think is the most important factor?

Ryukoku Students: We think the preventative focus is the most important.

Grand Valley students: do you think more guns in Japan would raise the crime rate.

Ryukoku Students: no but I think it might increase the suicide rate. Given the amount of police suicides using firearms in Japan (Japanese police officers carry guns, thus have ready access).

An interesting thought prompted by this question, is to what extent would Japanese culture and society be effected by an increase of guns in the population? Overall, there was an agreement in the room that more guns would not immediately generate more crime. But the discussion left me thinking about the long-term effects of such drastic change in regulation.

And interesting question was raised by visiting scholar: are police respected in your country?

A Grand Valley student cited his desire to enter the police force in America, and the negative reaction of his family and friends. He noted himself that the police force in America was in need of some level of change, and wanted to effect that from within. But challenged the overwhelming negative perception, noting the media obsession with showing the “bad apples” of the force.

A Ryukoku student replied with her own ambition to become a police officer. And how she had been met with encouragement her entire life.

The honest and heartful answers were inspiring and met with a round of applause each. The ability of the students to be vulnerable and provide their own experience was great to see.

I also asked a question: did you find any similarities between Japan and America in your research process.

I found the response pleasing, the Grand Valley students noted in their research process they wanted to avoid direct comparison. Which is always tempting when looking at another culture. Comparative research is always a delicate endeavour. Instead, they had focused on understanding the conditions of Japan without considering their own to any significant extent.

【補注】

*1. グランドバレー州立大学は米国のミシガン州で2番目に大きな総合大学です。同大学の犯罪学・刑事司法・法学部(School of Criminology, Criminal Justice, and Legal Studies)は、犯罪学や法学のみならず日本の警察学校に相当するコースを開設するなど、実務家養成に大きく寄与しています。

*2 【関連記事】第34回CrimRC(犯罪学研究センター)公開研究会を開催【犯罪学研究センター】

*3. 年齢犯罪曲線:ある年に出生した者等、特定の集団における非行・犯罪の発生率や発生頻度を縦軸に、年齢を横軸にプロットしたグラフのこと。このグラフから「非行・犯罪を行う者の率はおおむね10代前半から増加し始め10代半ばから後半にかけてピークを迎え、その後急激に減少していく」という傾向がわかる。この傾向は、時代・地域・人種などによってほとんど左右されない普遍性をもつものとして注目されている。

参考

小板清文「年齢犯罪曲線から見た非行と犯罪」、『徳島文理大学研究紀要』98巻(2019年)21〜33頁 >>リンク(J-stage)

法務総合研究所「青少年の立ち直り(デシスタンス)に関する研究」、『法務総合研究所研究部報告』58、(2018年)https://www.moj.go.jp/housouken/housouken03_00096.html (法務省)

上記報告書PDFの3頁