犯罪学研究センター公開研究会「グッドライフモデルに関する調査報告会」

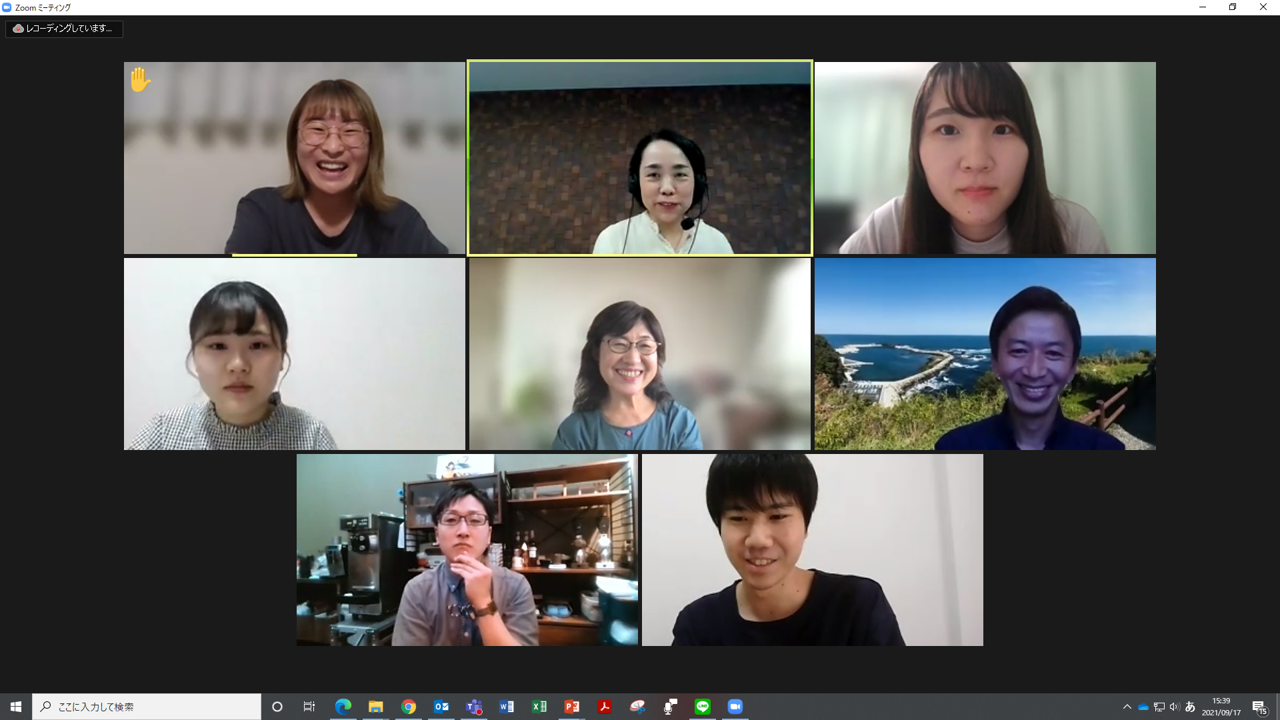

龍谷大学 犯罪学研究センター(CrimRC)は、10月29日(金)に下記のオンライン研究会を開催します。

【>>お申込みフォーム】

※申込期限:開催当日17:00

「グッドライフモデルに関する調査報告会」

〔日 時〕:2021年10月29日(金)18:00-19:30

〔内 容〕:企画の趣旨(10分)、報告(45分)、質疑応答(35分)

〔形 式〕リモート(Zoom)/定員200名

〔報 告〕相澤 育郎 助教(立正大学法学部, 犯罪学研究センター嘱託研究員)

【報告タイトル】

「日本におけるグッドライフモデルの適用可能性:NPO法人マザーハウスと共同で行った調査結果から」

【要旨】

2000年代初頭から提唱された犯罪者処遇・更生理論としてのグッドライフモデル(Good Lives model)は、諸外国の処遇実務に大きな影響を与えています。本研究発表では、NPO法人マザーハウスと共同で行ったアンケート調査の結果をもとに、このモデルの日本における適用可能性を検討します。

キーワード:Good Lives model、犯罪者の社会復帰

〔主 催〕龍谷大学 犯罪学研究センター(CrimRC)

─────────────────

【参考】

NPO法人マザーハウス 【インタビューレポート】「良き人生を生きる〜マザーハウスが実践するグッドライフ・モデルの可能性」(2020年4月20日)

https://motherhouse-jp.org/20200420interview/

※Zoomの視聴情報は、お申し込みフォームに入力いただいたメールアドレスに、【開催当日】にメールで連絡します。Zoom情報を、他に拡散しないようお願い

また、申し込み名とZoomの名前を合わせていただくようにお願いいたします。