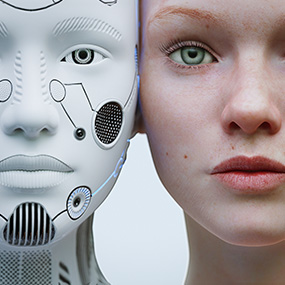

A medium for discussing society and oneself

We examine our rapidly changing world, use a multifaceted perspective to explore and address social issues, and question our own ways of being in the modern age.

Thoughts behind BEiNG

BEiNG is derived from “being”: a way of existence. The center letter “i” is written in lowercase to represent the self (I) existing in the midst of the times, as well as to evoke an exclamation mark, expressing that various surprising realizations and discoveries are hidden in this medium.